|

LINK to Part I Written by Catherine Savage Pulsipher; originally typed & arranged by Mabel Boyd Royal-Steen. typed & transcribed by Larry Spurling; arranged & compiled the Stump Ranch, Dan Royal © |

Skagit County's Own Gold RushReading on this Gold Rush period adds a new perspective and reason as to what brought Alex and Mary Boyd out from Nebraska. We've always stated in the family histories that Etta was always writting letters to her sister Mary Boyd encouraging her family to come out to Gods Country, but this minor Gold Rush must have been inviting to Alex Boyd who did file a mineral claim in Birdsview on the south side of the river near their in-laws [when they moved here in 1882]. Keep in mind looking at the above photos by Darius Kinsey that the majority of Skagit County looked just like this. When Mary Boyd came to this country, she did not like all the trees and felt claustrophobic by them, having grown up in the mid-west with wide open spaces. It took years and a couple generations if not more to produce the [bulk of] cleared farm land you might see on a drive around Skagit County. Skagit County also had natural prairies with great soil for agriculture. The mineral claim [gold, silver, coal, etc.] for the Boyd family turned out to be a bust, as most did for the couple thousand of miners who looked for riches during this time period; most if not all of these folks left the Upper Skagit by the mid 80's. While the homestead on the south side of the Skagit River from Birdsview has been in the Savage family since 1878, the Boyd's went down river by 1885. They did have a creek named after them though. I don't know if this story has seen print anywhere else, but I'm pleased to post it at the Stump Ranch, an archive for all things from cousins Kate Savage and Mabel Boyd. Excerpts from... MARKETING THE WILDERNESS: [below with link to NORTH CASCADES NATIONAL PARK website] were transcribed by Larry Spurling and gives a terrific overview and introduction to the story. |

This photo [pg. 106] from the Skagit County Historical Society Series- "Last Frontier in the North Cascades" by Will D. Jenkins. Ruby Creek enters from the high Cascades at lower right in the photo. |

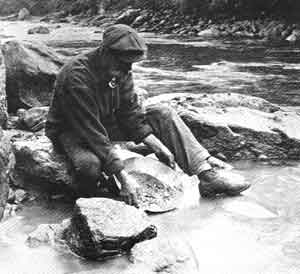

Again from the Skagit County Historical Society Series- "Last Frontier in the North Cascades" by Will D. Jenkins. PANNING GOLD [pg. 107] ...One of the few pictures ever taken of John McMillan, Ruby Creek pioneer packer and miner who came into the Upper Skagit from Ontario in 1883. McMillan had a homestead on Big Beaver Creek and for many years ran a roadhouse at the junction of the Ruby and Upper Skagit trails. Both photos from the Thompson collection. |

|

Written by Catherine Savage Pulsipher; originally typed & arranged by Mabel Boyd Royal-Steen; typed & transcribed by Larry Spurling; arranged & compiled the Stump Ranch, Dan Royal © LINK to Part I |